The EdTech industry has given rise to an abundant selection of language learning solutions: mobile technologies, video-based learning, social learning, VR learning, gamification, AI-backed learning, and so on. These categories can roughly be divided into synchronous and asynchronous learning (live learning or e-learning). The term "EdTech" is short for education technology and encompasses the combined use of computer hardware, software, and educational theory and learning.

Arguably the most futuristic field among these approaches is AI-based learning. With the ever-hopeful idea out there that AI can substitute human labor, and aid in translation or pronunciation, I like to focus on another angle: what research in the field can potentially teach us about our own inner workings of language acquisition.

Chomsky, Neural Networks and Language Learning

Noam Chomsky’s theory of an inherent universal grammar (普遍文法) template in the human brain has been challenged by findings in AI research utilizing two gigantic deep-learning neural networks, GPT-3 and GPT-2. The AI language learning models which seem to work similarly to the human brain have no inherent built-in grammar template, yet the neural networks were able to form perfectly correct sentences by exposure alone. In other words, no initial grammar framework seemed to be at work that helped these neural networks to absorb language input, interpret the information and correct sentences. The neural networks seemed to learn by interaction.

Based on the research evidence, the idea that grammar is the learning tapestry of language has been questioned by cognitive scientists and linguists and a different model called the usage-approach has been introduced. The theory suggests that children use abilities such as categorizing, building connotations, analogies, and guessing intentions to build an understanding of language.

A Behavioral Approach to Language Learning

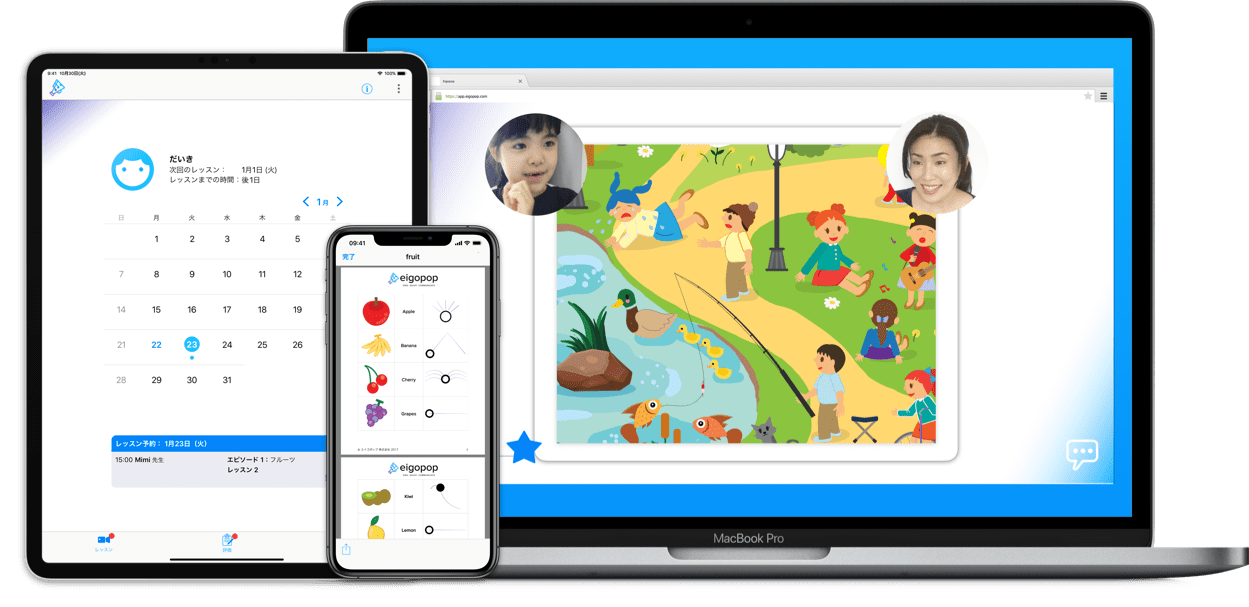

Considering today’s different approaches to English learning the question of what kind of learning approach is the most effective, and for what situation, age, and learning goal. There are the Juku type and Eikaiwa learning approaches. Online, there is the “social interaction with foreigners” approach, the “experience English” approach, there is the “bilingual approach.”

When it comes to the social interaction and experience approach as in “speak to anyone around the world anytime” I would say that this can be exciting and gives a chance to speak to real foreigners, but the question remains how well suited this is if the opposite cannot explain what is being learned.

When it comes to academic English teaching, some sources even argue that there is a lot of money being wasted. While I would agree with some points such as blindly memorizing and repeating phrases doesn’t train one’s ability to communicate in a foreign language (see here own article link) there are of course many other factors at play that separate effective learning from less effective learning. One thing remains clear, though – I have not seen any country that is more well-equipped with solutions to learn English than Japan.

Getting back to learning approaches, I think that beyond academic standards and technology-aided solutions there is another approach. That is to look at language learning as a behavioral approach and in my opinion one very important, and often ignored, ingredient of English language learning.

Like the idea that language and culture are inseparable, acquiring a language influences one’s perception and behavior. This might go either direction: language influences perception, vice versa encouraging a different perception lets a student learn a second language easier.

So, what is at the heart of the English language as spoken today? I would argue it’s individualism and the ability to express analytically and emotionally. Unfortunately, English is also the most unpredictable language out there Encouraging and adapting behavioral norms that come with a language cannot be learned through grammar learning, or staged conversation only. Because actual communication is missing. Well, how does a child start then? Doesn’t vocabulary and the ability to repeat phrases come first? I would argue that if it comes to be ready for standardized tests then yes. Memorizing is the shortest way. I also believe it’s the quickest route to forgetting what you studied and / or stalling in real conversation.

Language Learning Requires Interaction

Communication is often chaotic, and the main point of conversing is to get a point across. Sometimes it takes longer and sometimes shorter. But the very nature of communicating is to convey information.

Children should be exposed to learning in an engaging environment along with two-way communication. At first, that environment should be structured and predictable, and the second language starts to take root and can be produced more and more autonomously, the learning environment can become more unpredictable with a higher focus on independent speech production. But children should also learn to adapt the underlying implicit behavior aka thought processes of a language. English is both an analytical and emotional language. Denying these implicit socio-cultural tendencies might be denying full understanding and integration of the language, something that grammar learning and wrote memorization cannot achieve alone.

Five Steps To Real Language Acquisition

For children, language acquisition takes place on five levels:

1. Pre-production

Minimal comprehension, no verbalization combined with body language.

2. Early Production

Limited comprehension, keywords, and present tense sentences.

3. Speech Emergence

Good comprehension, simple sentences, grammar errors, and testing.

4. Intermediate Fluency

Very good comprehension of more complex sentence structures.

5. Advanced Fluency

Excellent comprehension with very few grammatical errors.

The five steps above can apply to any student at any given age. The key point is that comprehension takes place even before grammar. The intention and the will to express come before grammar. Communication takes place before grammar accuracy.

As might be proven by discoveries in AI language acquisition, language might not be born out of hierarchical grammar structures, and in its extreme, might not even require grammar understanding to speak thus refuting Chomsky’s widely accepted universal grammar rule but acquisition can be based on continued and exposure alone. Especially for children, language is not understood on an intellectual level but foremost on an abstract and emotional level, tested through communication.

Conclusion

Personally, I am convinced that training the senses, forming connotations, and two-way engagement is a highly effective way of acquiring language. We take in and experience the world with several senses. We tend to evaluate that experience through output. That is a two-way street. Blindly learning the four skills of reading listening writing speaking in a passive-only way in staged environments that allow no mistakes is not acquisition. Real language is far more chaotic, unpredictable and both analytical and reactive. It requires an intent to interact and perhaps a spirit of experimentation.

For language learning, I believe these are certain ingredients that come before grammar rules: observation, listening, exploring, experimenting, and asking questions.

In the next article, I further explore whether AI can really help children acquire natural language.